Preview of The Financial System Limit by David Kauders This preview is extracted from Chapter 1 and is the same in all editions When someone borrows money to put food on the table, they are in financial difficulty. When they have no hope of even paying the mounting interest bill, let alone repaying their debt, they are bust. This can also happen to a country, when so many people are in financial difficulty that there is no hope of the indebted population honouring its debts even if some people within it are debt-free. In this situation the said country has reached its financial system limit. Neither action by the individual, nor policy change by the authorities, can work off the debt because too much is being spent on paying interest. The underlying problem will manifest itself in many ways: curtailed business activity; inability of consumers to keep spending; falling prices of assets that were propped up by easy credit; almost continual recession with only brief flashes of recovery. The financial system limit of any society is the debt level at which repayment ceases to be viable.It is customary for economic statisticians to define highly indebted countries according to their government debt levels. However, for the purposes of this book, it is total debt that matters. Total debt is the sum of government debt, corporate plus banking system debt and personal debt. Personal debt itself consists of overdrafts, bank loans, mortgages and credit card debt.Of the 36 current members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 28 feature in a list of countries having high levels of personal debt. Personal debt is a developed-country problem. Prosperity has been bought, literally, on credit...We have become used to central banks being able to conjure recoveries out of recessions. Each time a downturn has occurred, it has been swept away but downturns became deeper as the natural economic cycles of the past were augmented by policy-driven cycles. For example, in the United Kingdom, according to the Office for National Statistics, GDP fell by 4.2% in 2009, whereas in 1991 it only fell by 1.1%. In GDP terms, the dot com “bust” was represented by a lower growth rate.3Serious financial and business journals have carried many reports and opinions about how central banks need to find new ways to counteract the recession that is unfolding around the world. The fashionable proposal is to use fiscal policy (that is, tax cuts and increased government expenditure) to stimulate economic activity. Such a policy can have no lasting benefit, for three reasons:

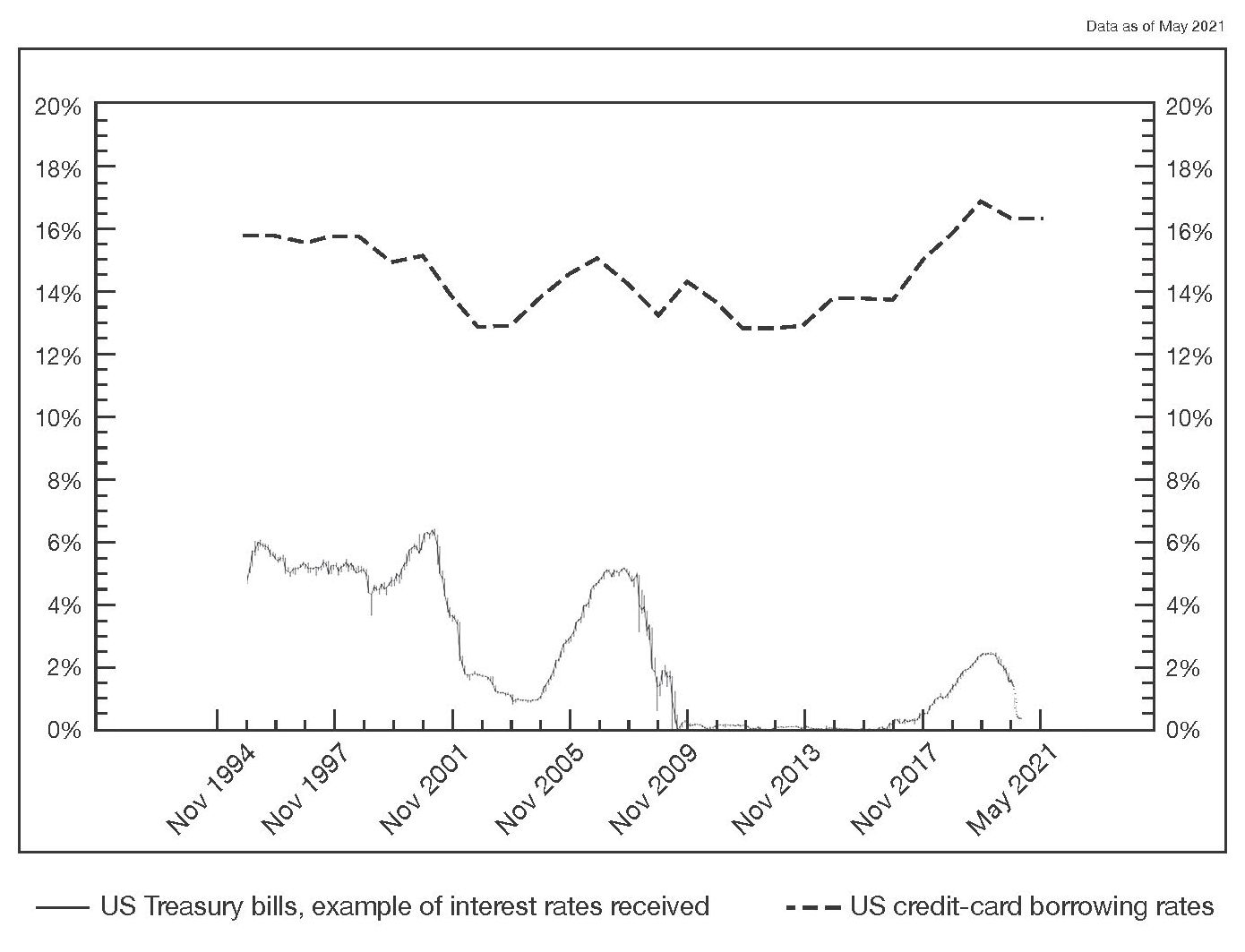

Over the past quarter of a century, rates paid to depositors have collapsed, yet rates paid by borrowers have stayed comparatively high. Figure 1 contrasts three-month US Treasury Bill rates (a proxy for interest paid to depositors) with the average cost of US credit card debt including financing charges:4

Figure 1: Paying more to the banking systemComparing paid and earned interest rates in this way reveals the cost of credit. From 1994 to 2001, the difference between the two rates was around 9% to 10%. In 2003, after the dot com crash, deposit rates hit new lows, with Treasury Bills only paying 0.81%. By 2005, credit-card borrowers were typically paying 15%: the difference had risen slightly. The credit crunch then drove Treasury Bills down to nil yield but credit card rates climbed, and at May 2021, borrowers were paying 16% above Treasury bill rates.Debt repayment has a real cost because inflation is so low. When real interest rates are positive and rates paid by borrowers exceed the inflation rate, borrowing consumes financial resources. For example, when inflation is 1% and credit-card borrowing costs 13%, the real rate of interest is 12%. Prior to the era of monetary management by central banks, real interest rates were usually 2% to 3%.Symptoms of debt problems caused by excessive interest costs vary by country. In many cases, they can be measured directly by statistics such as consumer loan defaults. In Britain, food bank use is an indirect measure of debt problems.Following the 1987 stock market crash, the credit floodgates were opened wide to encourage more borrowing. When continuing that policy proved ineffective after the millennium boom and bust, quantitative easing was invented to push credit into the Japanese economy. This was later copied by other central banks although the methodology is now seen as ineffective. Instead of contriving ever more extreme measures to expand credit, why not ask what is preventing continued economic growth?It is impossible for debt to expand to infinity because the cost of servicing it would then also be infinite. The financial system limit is determined by the cost of borrowing. It is best defined as the proportion of economic output spent on interest on total debt, above which that debt can no longer be repaid in full...A logical proofExistence of the financial system limit can be proved by logic:1. Postulate that it does not exist and therefore debt can expand to infinity.2. No matter how low interest rates charged to borrowers may go, any percentage of infinity is itself infinity. Therefore if debt can expand to infinity, interest paid must also expand to infinity.3. Interest has to be defrayed from what is earned. Earnings can only be achieved by selling goods or services at a price others can afford. Therefore paying infinite interest requires trading an infinite supply of goods and services.4. But an infinite supply of goods and services for sale can only be achieved if resources of people and nature are themselves infinite.5. Since the supply of raw materials is finite and an infinite population could not feed itself, the proposition that debt can expand to infinity cannot be true...* * * We hope you enjoyed reading this extract.

For footnotes, please refer to the published book

|